This was my typical work day a year ago:

- Grab a bowl of cereal or whatever there is in the fridge for breakfast.

- Run to the subway and grab a coffee on my way to work.

- A bagel with cream cheese, a shawarma, a muffin or whatever I could find at lunch. This would coincide with my third cup of coffee of the day. Other times, I went to a restaurant for a business meeting and this would be my main meal of the day.

- Go to a networking evening event and eat whatever they have. Pretzels, beers, coffee, chips, you name it. If there is no event, I would otherwise pick up a hefty meal from a neighboring restaurant on my way home.

Repeat this five days a week and you have a recipe for disaster. It is a diet composed of processed foods, refined carbs and inflammatory foods that lead to obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, or worse.

The sad state of affairs prompted me to get Mealime, a free app available on Android and iPhone. It is also available on the web, but this 9 months review only covers the mobile app.

I find Mealime is an excellent meal and nutrition planner. Akin to having a training plan, meal planning allows you to have consistent nutrition that you can easily track, and improve later on. This is good for those with serious athletic goals, who want to have good health or those who have chronic diseases.

Without meal planning, you are more likely to improvise, eat out, and deviate from health goals. It also makes food tracking difficult. Who would wish to list all ingredients in their food if every meal was different? No one.

How it works

Mealime asks for your food preferences on setup. Classics is for most people. Low Carb means limited glucides and instead more healthy fats. Vegetarian is zero meat. There is also Paleo, Pesceterian and Flexitarian, options I didn’t know about.

My goal was to control blood sugar and insulin levels so I chose low carb.

Mealime also asks for allergies and ingredients you dislike. I dislike for example turnips.

After choosing a menu type, it then asks you how many meals you wish to prepare.

If you don’t like a dish, you can swipe left, until you have all the meals you want.

The app then shows a summary of ingredients. I find this very practical when doing groceries.

You know exactly what to get and what not to get. This reduces my stress, and I feel like a master chef

Hey, we are cooking!

Prior to Mealime, my cooking skills were limited to basic omelettes or making batches of kitchen breasts. Naturally, I was apprehensive. Disaster, anyone?

I was positively surprised to find that Mealime dishes are not difficult to make. They take on average 40 minutes to make and never require any special talent or instruments. It takes a good knife, a pan and an oven. And a smile

Since then, I changed to a better chef’s knife, a good skillet and more spices but you can always manage with what you have at home.

Easy Meal Planning for the week

I do groceries on weekends, then cook a Mealime dish in the evening. I have a delicious dinner and put the rest in containers. They usually last 3 days, and usually I cook again mid-week.

If we take the baseline of 40 minutes for meal preparation, that means every dish takes me 40 / 7 ~ 6 minutes to make. Surely beats going to a take-out restaurant!

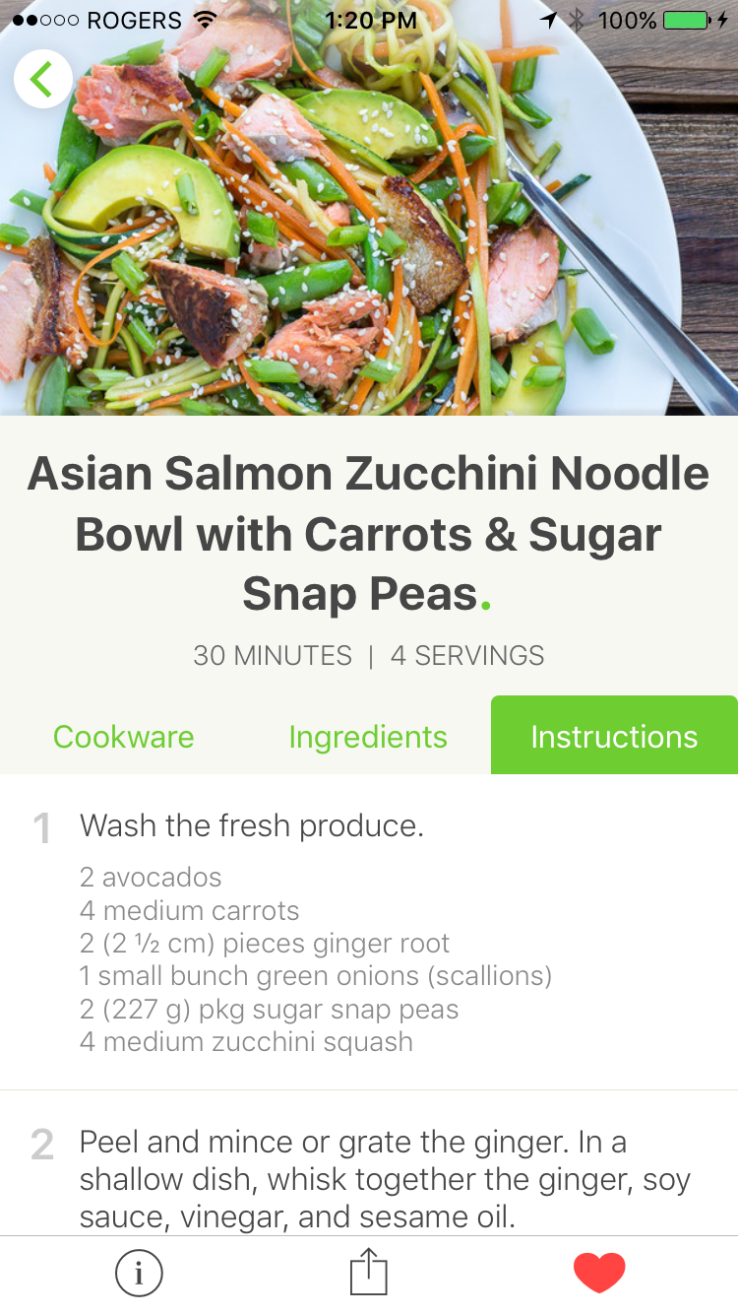

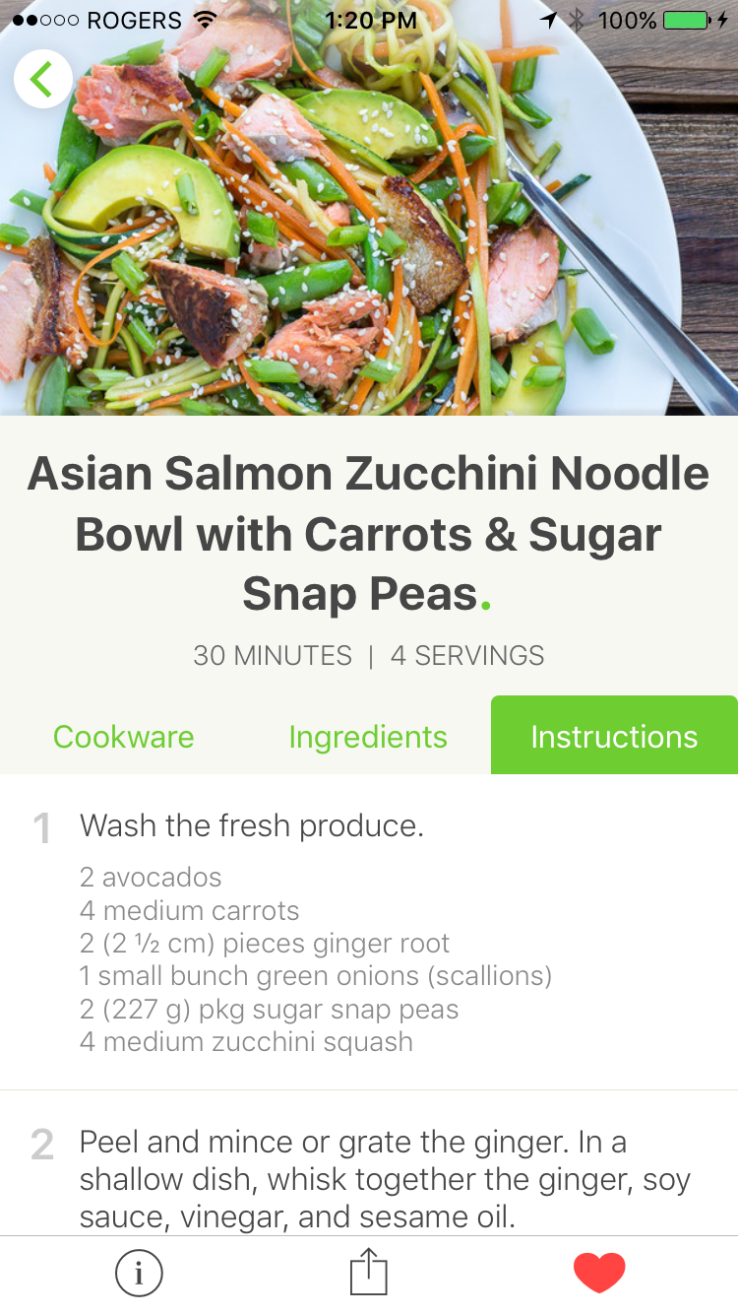

If you favorite a dish, it is always available through a shortcut. For instance, I often make wild atlantic salmon with zucchini and carrots. You can then add the recipe in MyFitnessPal, which means food tracking takes only a few seconds. It’s a nice streamlined process to take control of your nutrition intake.

Dramatic Results

By following the low carb option, and commuting by bike, I lost a lot of weight in a few months (~7kgs). The loss was dramatic and many friends and acquittances could not believe it.

The biggest benefit I find however is great overall energy, eating more vegetables, and learning to appreciate good food cooked at home. This is a life skill I underestimated previously and I am glad Mealime helped.

It also makes my life easy, and lets me invest my time elsewhere.

A Perfect App?

I have not used other food apps so I can’t say on how it compares to other competitors. I can say however Mealime is great for those with limited time and want to cook healthy meals. It provides nutritious fuel for my running and daily work and can wholly recommend it. Download it and give it a go !

Feature

Feature

We know about the issue of slowed metabolism after weight loss due to the lean muscle mass loss that goes along with fat loss. This is one reason why higher protein/low carb diets work better than low fat diets; because muscle mass is maintained better. Well, new information from Diabetes in Control backs up what some of us know intuitively or may have experienced personally….

We know about the issue of slowed metabolism after weight loss due to the lean muscle mass loss that goes along with fat loss. This is one reason why higher protein/low carb diets work better than low fat diets; because muscle mass is maintained better. Well, new information from Diabetes in Control backs up what some of us know intuitively or may have experienced personally….

I’m delighted that The BMJ has stood by this article and decided against retraction. Two outside reviewers judged that the criticisms of the piece did not merit its retraction, and in the end, the corrections made by The BMJ do not, in my view, materially undermine any of the article’s key claims. This article therefore stands as one of the most serious ever, peer-reviewed critiques of the expert report for the US Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs).

The importance of the DGAs, and therefore of this article, should not be understated (and indeed was recognized by many in the mainstream media when the article was published). The DGAs have long been considered the “gold standard,” informing the US food supply, military rations, US government feeding assistance programs such as the National School Lunch Program which are, altogether, consumed by 1 in 4 Americans each month, as well as the guidelines of professional societies and governments around the world, and eating habits generally.

Yet rates of obesity began to shoot upwards in the very year, 1980, that the DGAs were introduced, and the diabetes epidemic began soon thereafter. A critically important yet little understood issue is why the DGAs have failed, so spectacularly, to safeguard health from the very nutrition-related diseases that they were supposed to prevent.

In documenting fundamental failures in the science behind the DGAs, this article offers new insights; It establishes that a vast amount of nutrition science funded by the National Institutes of Health and other governments worldwide has, for decades, been systematically ignored or dismissed, and that therefore, that the DGAs are not based on a comprehensive reviews of the most rigorous science. Incorporating this long-ignored relevant science would likely lead to fundamentally different DGAs and could very well be an important step in infusing them with the power to better fight the nutrition-related diseases.

A fundamental question is why 170+ researchers (including all the 2015 DGA committee members, or “DGAC”), organized by the advocacy group, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), would sign a letter asking for retraction. After all, in the weeks following publication, any person had the opportunity to submit a “Rapid Response” to the article, and both CSPI and the DGAC did so, alleging many errors. I responded to them all in my Rapid Response. This is the normal post-publication process.

Yet after all this, CSPI returned for a second round of criticisms, recycling two of the issues (CSPI points #3 and #10) that I had already addressed in my Rapid Response (and which had required no correction), adding another 9 (one of which, #4, contained no challenge of fact), and demanding that based on these alleged errors, the article be retracted. CSPI then circulated this letter widely to colleagues and asked them to sign on.

This lack of substance in the retraction effort seems to point to the reality that it was first and foremost an act of advocacy—a heavy handed attempt to silence arguments with which CSPI, a longtime supporter of the Dietary Guidelines and its allies disagree.[ footnote 1] And this applies not just to the retraction letter but to other CSPI efforts to stifle alternative viewpoints. Earlier this year, for example, I was dis-invited from the National Food Policy Conference after CSPI, together with the USDA official in charge of the Dietary Guidelines, threatened to withdraw if I were included, details of which are reported here and which a Spiked columnist called an act of “censorship.”

It’s important to note that I am not the only person disturbed by the lack of rigorous science underpinning our dietary guidelines. Numerous scientists around the world have expressed concern about the science. And indeed, this consternation is shared by no less than the US Congress, which held a hearing on Oct 7, 2015 to address its serious doubts about the DGAs. Such was this concern that last year that Congress mandated the first-ever major peer-review of the DGAs, by the National Academy of Medicine. Congress appropriated $1 million for this review, and it additionally stipulated that all members of the 2015 DGA committee recuse themselves from the process.

What is the dangerous information challenging the DGAs that cannot be heard on a conference panel nor published in a peer-reviewed journal?

The major findings of this article are that:

1. The DGAC’s finding that the evidence of a “strong” link between saturated fats and heart disease was not clearly supported by the evidence cited. (Note that as of last year, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada no longer limits saturated fats. Note, also, that Frank Hu, the Harvard epidemiologist in charge of the DGAC review on saturated fats, was an energetic promoter of the retraction letter against my article that critiqued his review, according to emails obtained through FOIA requests);

2. Successive DGA committees have for decades ignored or dismissed a large body of rigorous (randomized controlled trial) literature on the low-fat diet, on more than 50K subjects, collectively finding that this diet is ineffective for fighting obesity, diabetes, heart disease or any kind of cancer;

3. Although the DGAs have for decades recommended avoiding saturated fats and cholesterol to prevent heart disease, no DGA committee has ever directly reviewed the enormous body of rigorous (government-funded, randomized controlled trials) evidence, testing more than 25,000 people, on this hypothesis. Many reviews of this data have concluded that saturated fats have no effect on cardiovascular mortality;

4. The DGAC ignored a large body of scientific literature on low-carbohydrate diets (including several “long term” trials, of 2-years duration) demonstrating that these diets are safe and highly effective for combatting obesity, diabetes, and heart disease;

5. The Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) set up by USDA to do systematic reviews of the science did not meet its own standards for its review of saturated fats in 2010;

6. Although the DGAC is supposed to consult the NEL to conduct systematic reviews of the science, the 2015 DGAC did so for only 67% of the questions that required systematic reviews;

7. For a number of key reviews, the 2015 DGAC relied on work done in part by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, which are private associations supported by industry and therefore have a potential conflict of interest;

8. The DGAs, for the first time, introduce the “vegetarian diet” as one of its three, recommended “Dietary Patterns,” yet a NEL review of this diet concluded that the evidence for this its disease-fighting powers is only “limited,” which is the lowest rank of evidence assigned for available data;

9. The DGA’s three recommended “Dietary Patterns” are supported by only limited evidence. The NEL review found only “limited” or “insufficient” evidence that the diets could combat diabetes and only “moderate” evidence that the diets can help people lose weight. The report also gave a strong rating to the evidence that its recommended diets can fight heart disease, yet here, several studies are presented, but none unambiguously supports this claim. In conclusion, the quantity of recommended diets are supported by a small quantity of rigorous evidence that only marginally supports claims that these diets can promote better health than alternatives;

10. The DGA process does not require committee members to disclose conflicts of interest and also that, for the first time, the committee chair came not from a university but from industry;

11. The 2015 DGAC conducted a number of reviews in ways that were not systematic. This allowed for the potential introduction of bias (e.g., cherry picking of the evidence).

This last claim, on the systematic nature of the DGAC reviews, is the subject of the corrections published in The BMJ this week, and refer to CSPI points #1, #2, #7, and #8 (two of which are statements in the text and two of which are in the supporting tables). I am grateful to have had the opportunity to work with The BMJ on developing this notice.

The BMJ has placed a word limit on my response. For the rest of this comment, please see: http://thebigfatsurprise.com/comment-bmj-correction-notice/

Footnote 1

CSPI has fought for decades to eliminate saturated fats from the American food supply (so much so, that throughout the late 1980s, CSPI advocated for replacing saturated fats with trans fats and succeeded in driving up consumption of trans fats to historic levels, as described in The Big Fat Surprise, pp.227-228). CSPI has also long advocated for shifting away from animal foods containing saturated fats, towards a plant-based diet based on grains and industrial vegetable oils. The researchers who joined CSPI in signing the letter are largely adherents to this view; many have participated in generating the science that has been used to support the hypothesis that fat and cholesterol cause heart disease, and it is upon this hypothesis that the Guidelines have been based.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that I am the author of The Big Fat Surprise (Simon & Schuster, 2014), on the history, science, and politics of dietary fat recommendations. I have received modest honorariums for presenting my research findings presented in the book to a variety of groups related to the medical, restaurant, financial, meat, and dairy industries. I am also a board member of a non-profit organization, the Nutrition Coalition, dedicated to ensuring that nutrition policy is based on rigorous science.